Getting Started

By the end of this tutorial, you will have created a Conduit application that serves fictional heroes from a PostgreSQL database. You will learn the following:

- Run a Conduit application

- Route HTTP requests to the appropriate handler in your code

- Store and retrieve database data

- Write automated tests for each endpoint

- Require authorization for HTTP requests

Installation

Make sure that your system has the latest stable version of dart installed. Find the version suited for your operating system here: https://dart.dev/get-dart

Install the conduit command line tool by running the following command in your shell:

pub global activate conduit

Creating a Project

Create a new project named heroes by entering the following in your shell:

conduit create heroes

This creates a heroes project directory with a default server implementation populating it.

Handling HTTP Requests

In your browser, navigate to http://conduit-tutorial.conduit.dart.io. This browser application is a 'Hero Manager' - it allows a user to view, create, delete and update heroes. (It is a slightly modified version of the AngularDart Tour of Heroes Tutorial.) It will make HTTP requests to http://localhost:8888 to fetch and manipulate hero data. The application you will build in this tutorial respond to those requests.

!!! warning "Running the Browser Application Locally" The browser application is served over HTTP so that it can access your Conduit application when it runs locally on your machine. Your browser may warn you about navigating to an insecure webpage, because it is in fact insecure. You can run this application locally by grabbing the source code from here.

In this first chapter, you will write code to handle two requests: one to get a list of heroes, and the other to get a single hero by its identifier. Those requests are:

GET /heroesto the list of heroesGET /heroes/:idto get an individual hero

!!! tip "HTTP Operation Shorthand" The term GET /heroes is called an operation. It is the combination of the HTTP method and the path of the request. Each operation is unique to an application, so your code is segmented into units for each operation. Sections with a colon, like the ':id' segment, are variable: they can be 1, 2, 3, and so on.

Controller Objects Handle Requests

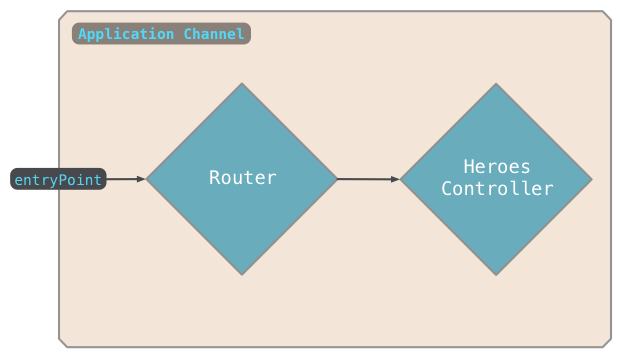

Requests are handled by controller objects. A controller object can respond to a request. It can also take other action and let another controller respond. For example, it might check if the request is authorized, or send analytical data to some other service. Controllers are composed together, and each controller in the composition performs its logic in order. This allows for some controllers to be reused, and for better code organization. A composition of controllers is called a channel because requests flow in one direction through the controllers.

Our application will link two controllers:

- a

Routerthat makes sure the request path is/heroesor/heroes/:id - a

HeroesControllersthat responds with hero objects

Your application starts with a channel object called the application channel. You link the controllers in your application to this channel.

Each application has a subclass of ApplicationChannel that you override methods in to set up your controllers. This type is already declared in lib/channel.dart - open this file and find ApplicationChannel.entryPoint:

@override

Controller get entryPoint {

final router = Router();

router

.route('/example')

.linkFunction((request) async {

return Response.ok({'key': 'value'});

});

return router;

}

When your application gets a request, the entryPoint controller is the first to handle it. In our case, this is a Router - a subclass of Controller.

!!! tip "Controller Subclassing" Every controller you use will be a subclass of Controller. There are some controller subclasses already in Conduit for common behaviors.

You use the route method on a router to attach a controller to a route. A route is a string syntax that matches the path of a request. In our current implementation, the route will match every request with the path /example. When that request is received, a linked function runs and returns a 200 OK response with an example JSON object body.

We need to route the path /heroes to a controller of our own, so we can control what happens. Let's create a HeroesController. Create a new file in lib/controller/heroes_controller.dart and add the following code (you will need to create the subdirectory lib/controller/):

import 'package:conduit_core/conduit_core.dart';

import 'package:heroes/heroes.dart';

class HeroesController extends Controller {

final _heroes = [

{'id': 11, 'name': 'Mr. Nice'},

{'id': 12, 'name': 'Narco'},

{'id': 13, 'name': 'Bombasto'},

{'id': 14, 'name': 'Celeritas'},

{'id': 15, 'name': 'Magneta'},

];

@override

Future<RequestOrResponse> handle(Request request) async {

return Response.ok(_heroes);

}

}

Notice that HeroesController is a subclass of Controller; this is what makes it a controller object. It overrides its handle method by returning a Response object. This response object has a 200 OK status code, and it body contains a JSON-encoded list of hero objects. When a controller returns a Response object from its handle method, it is sent to the client.

Right now, our HeroesController isn't hooked up to the application channel. We need to link it to the router. First, import our new file at the top of channel.dart.

import 'controller/heroes_controller.dart';

Then link this HeroesController to the Router for the path /heroes:

@override

Controller get entryPoint {

final router = Router();

router

.route('/heroes')

.link(() => HeroesController());

router

.route('/example')

.linkFunction((request) async {

return Response.ok({'key': 'value'});

});

return router;

}

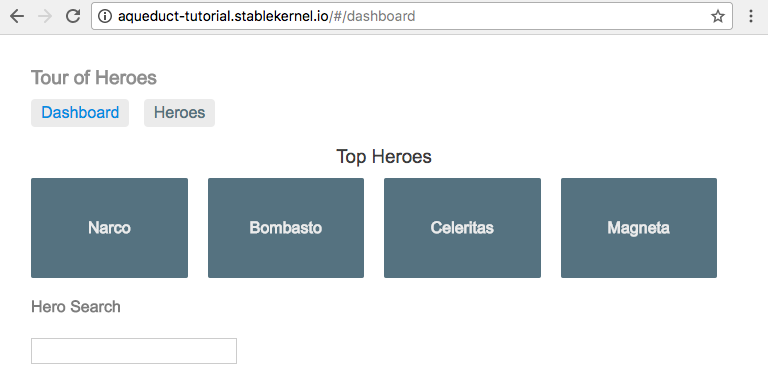

We now have a application that will return a list of heroes. In the project directory, run the following command from the command-line:

conduit serve

This will start your application running locally. Reload the browser page http://conduit-tutorial.conduit.dart.io. It will make a request to http://localhost:8888/heroes and your application will serve it. You'll see your heroes in your web browser:

Screenshot of Heroes Application

You can also see the actual response of your request by entering the following into your shell:

curl -X GET http://localhost:8888/heroes

You'll get JSON output like this:

[

{"id":11,"name":"Mr. Nice"},

{"id":12,"name":"Narco"},

{"id":13,"name":"Bombasto"},

{"id":14,"name":"Celeritas"},

{"id":15,"name":"Magneta"}

]

You'll also see this request logged in the shell that you started conduit serve in.

Linking Controllers

When a controller handles a request, it can either send a response or let one of its linked controllers handle the request. By default, a Router will send a 404 Not Found response for any request. Adding a route to a Router creates an entry point to a new channel that controllers can be linked to. In our application, HeroesController is linked to the route /heroes.

Controllers come in two different flavors: endpoint and middleware. Endpoint controllers, like HeroesController, always send a response. They implement the behavior that a request is seeking. Middleware controllers, like Router, handles requests before they reach an endpoint controller. A router, for example, handles a request by directing it to the right controller. Controllers like Authorizer verify the authorization of the request. You can create all kinds of controllers to provide any behavior you like.

A channel can have zero or many middleware controllers, but must end in an endpoint controller. Most controllers can only have one linked controller, but a Router allows for many. For example, a larger application might look like this:

@override

Controller get entryPoint {

final router = Router();

router

.route('/users')

.link(() => APIKeyValidator())

.link(() => Authorizer.bearer())

.link(() => UsersController());

router

.route('/posts')

.link(() => APIKeyValidator())

.link(() => PostsController());

return router;

}

Each of these objects is a subclass of Controller, giving them the ability to be linked together to handle requests. A request goes through controllers in the order they are linked. A request for the path /users will go through an APIKeyValidator, an Authorizer and finally a UsersController. Each of these controllers has an opportunity to respond, preventing the next controller from receiving the request.

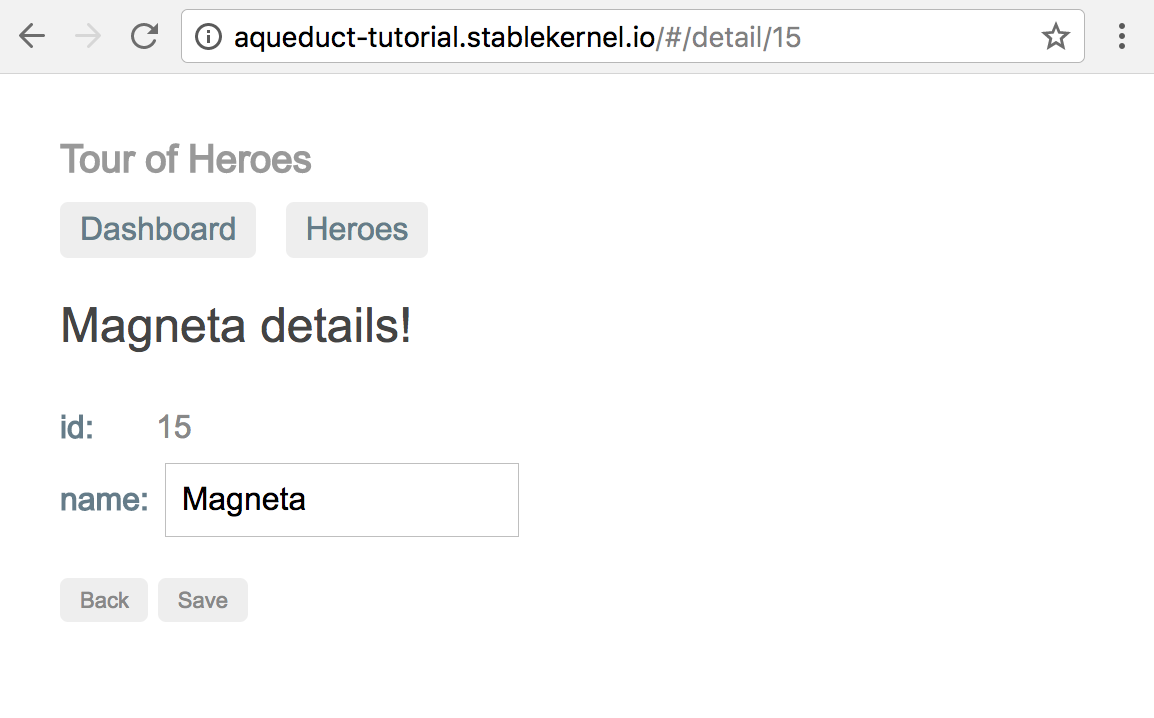

Advanced Routing

Right now, our application handles GET /heroes requests. The browser application uses the this list to populate its hero dashboard. If we click on an individual hero, the browser application will display an individual hero. When navigating to this page, the browser application makes a request to our server for an individual hero. This request contains the unique id of the selected hero in the path, e.g. /heroes/11 or /heroes/13.

Our server doesn't handle this request yet - it only handles requests that have exactly the path /heroes. Since a request for individual heroes will have a path that changes depending on the hero, we need our route to include a path variable.

A path variable is a segment of route that matches a value for the same segment in the incoming request path. A path variable is a segment prefixed with a colon (:). For example, the route /heroes/:id contains a path variable named id. If the request path is /heroes/1, /heroes/2, and so on, the request will be sent to our HeroesController. The HeroesController will have access to the value of the path variable to determine which hero to return.

There's one hiccup. The route /heroes/:id no longer matches the path /heroes. It'd be a lot easier to organize our code if both /heroes and /heroes/:id went to our HeroesController; it does heroic stuff. For this reason, we can declare the :id portion of our route to be optional by wrapping it in square brackets. In channel.dart, modify the /heroes route:

router

.route('/heroes/[:id]')

.link(() => HeroesController());

Since the second segment of the path is optional, the path /heroes still matches the route. If the path contains a second segment, the value of that segment is bound to the path variable named id. We can access path variables through the Request object. In heroes_controller.dart, modify handle:

// In just a moment, we'll replace this code with something even better,

// but it's important to understand where this information comes from first!

@override

Future<RequestOrResponse> handle(Request request) async {

if (request.path.variables.containsKey('id')) {

final id = int.parse(request.path.variables['id']);

final hero = _heroes.firstWhere((hero) => hero['id'] == id, orElse: () => null);

if (hero == null) {

return Response.notFound();

}

return Response.ok(hero);

}

return Response.ok(_heroes);

}

In your shell currently running the application, hit Ctrl-C to stop the application. Then, run conduit serve again. In the browser application, click on a hero and you will be taken to a detail page for that hero.

You can verify that your server is responding correctly by executing curl -X GET http://localhost:8888/heroes/11 to view the single hero object. You can also trigger a 404 Not Found response by getting a hero that doesn't exist.

ResourceControllers and Operation Methods

Our HeroesController is OK right now, but it'll soon run into a problem: what happens when we want to create a new hero? Or update an existing hero's name? Our handle method will start to get unmanageable, quickly.

That's where ResourceController comes in. A ResourceController allows you to create a distinct method for each operation that we can perform on our heroes. One method will handle getting a list of heroes, another will handle getting a single hero, and so on. Each method has an annotation that identifies the HTTP method and path variables the request must have to trigger it.

In heroes_controller.dart, replace HeroesController with the following:

class HeroesController extends ResourceController {

final _heroes = [

{'id': 11, 'name': 'Mr. Nice'},

{'id': 12, 'name': 'Narco'},

{'id': 13, 'name': 'Bombasto'},

{'id': 14, 'name': 'Celeritas'},

{'id': 15, 'name': 'Magneta'},

];

@Operation.get()

Future<Response> getAllHeroes() async {

return Response.ok(_heroes);

}

@Operation.get('id')

Future<Response> getHeroByID() async {

final id = int.parse(request.path.variables['id']);

final hero = _heroes.firstWhere((hero) => hero['id'] == id, orElse: () => null);

if (hero == null) {

return Response.notFound();

}

return Response.ok(hero);

}

}

Notice that we didn't have to override handle in ResourceController. A ResourceController implements this method to call one of our operation methods. An operation method - like getAllHeroes and getHeroByID - must have an Operation annotation. The named constructor Operation.get means these methods get called when the request's method is GET. An operation method must also return a Future<Response>.

getHeroByID's annotation also has an argument - the name of our path variable id. If that path variable exists in the request's path, getHeroByID will be called. If it doesn't exist, getAllHeroes will be called.

!!! tip "Naming Operation Methods" The plain English phrase for an operation - like 'get hero by id' - is a really good name for an operation method and a good name will be useful when you generate OpenAPI documentation from your code.

Reload the application by hitting Ctrl-C in the terminal that ran conduit serve and then run conduit serve again. The browser application should still behave the same.

!!! tip "Browser Clients" In addition to curl, you can create a SwaggerUI browser application that executes requests against your locally running application. In your project directory, run conduit document client and it will generate a file named client.html. Open this file in your browser for a UI that constructs and executes requests that your application supports.

Request Binding

In our getHeroByID method, we make a dangerous assumption that the path variable 'id' can be parsed into an integer. If 'id' were something else, like a string, int.parse would throw an exception. When exceptions are thrown in operation methods, the controller catches it and sends a 500 Server Error response. 500s are bad, they don't tell the client what's wrong. A 404 Not Found is a better response here, but writing the code to catch that exception and create this response is cumbersome.

Instead, we can rely on a feature of operation methods called request binding. An operation method can declare parameters and bind them to properties of the request. When our operation method gets called, it will be passed values from the request as arguments. Request bindings automatically parse values into the type of the parameter (and return a better error response if parsing fails). Change the method getHeroByID():

@Operation.get('id')

Future<Response> getHeroByID(@Bind.path('id') int id) async {

final hero = _heroes.firstWhere((hero) => hero['id'] == id, orElse: () => null);

if (hero == null) {

return Response.notFound();

}

return Response.ok(hero);

}

The value of the path variable id will be parsed as an integer and be available to this method in the id parameter. The @Bind annotation on an operation method parameter tells Conduit the value from the request we want bound. Using the named constructor Bind.path binds a path variable, and the name of that variable is indicated in the argument to this constructor.

You can bind path variables, headers, query parameters and bodies. When binding path variables, we have to specify which path variable with the argument to @Bind.path(pathVariableName).

!!! tip "Bound Parameter Names" The name of a bound parameter doesn't have to match the name of the path variable. We could have declared it as @Bind.path('id') int heroID. Only the argument to Bind's constructor must match the actual name of the path variable. This is valuable for other types of bindings, like headers, that may contain characters that aren't valid Dart variable names, e.g. X-API-Key.

The More You Know: Multi-threading and Application State

In this simple exercise, we used a constant list of heroes as our source of data. For a simple getting-your-feet-wet demo, this is fine. However, in a real application, you'd store this data in a database. That way you could add data to it and not risk losing it when the application was restarted.

More generally, a web server should never hang on to data that can change. While previously just a best practice, stateless web servers are becoming a requirement with the prevalence of containerization and tools like Kubernetes. Conduit makes it a bit easier to detect violations of this rule with its multi-threading strategy.

When you run a Conduit application, it creates multiple threads. Each of these threads has its own isolated heap in memory; meaning data that exists on one thread can't be accessed from other threads. In Dart, these isolated threads are called isolates.

An instance of your application channel is created for each isolate. Each HTTP request is given to just one of the isolates to be handled. In a sense, your one application behaves the same as running your application on multiple servers behind a load balancer. (It also makes your application substantially faster.)

If you are storing any data in your application, you'll find out really quickly. Why? A request that changes data will only change that data in one of your application's isolates. When you make a request to get that data again, its unlikely that you'll see the changes - another isolate with different data will probably handle that request.